Emeritus Funds Reports

Fall 2017 Anthropology Newsletter information

Rhett Lundy

The Emeritus Funds I received were used for attending a seminar on wolf research throughout the Midwest region of both the Unites States and Canada. I learned a great deal about the current status of wolves in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Ottawa, and Yellowstone National Park. This particularly relates to anthropology as it concerns faunal remains analysis, human-wolf interactions, and human involvement on the changing natural landscape of wolf territory. Particularly, it relates to human interference in protected, historical, wilderness areas. As I conducted field research on wolves in northern Minnesota last January, and will be a teaching assistant in January 2018 for the same study, this seminar was exceptionally helpful for improving my knowledge on human-wolf interactions and refreshing some previously known information. The research I focus on encompasses faunal remains analysis via kill site analysis, which provides insight into population dynamics, behavioral trends, changes in the landscape, etc. Through this examination, we can make assumptions about the lives of both wolves and their prey.

Misha Laurence

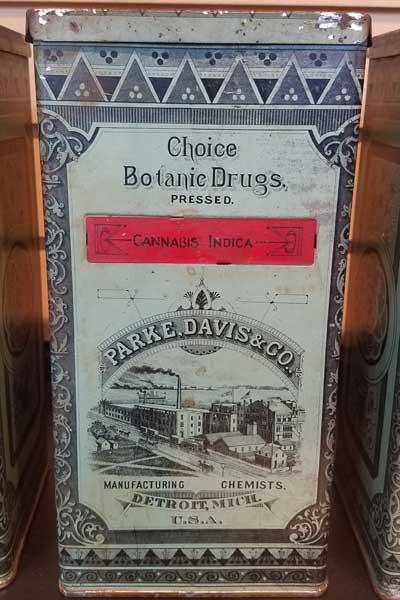

Medical cannabis is a hot topic in medicine, public health, and policy, but otherwise remains understudied in the social sciences. As a student from Washington State, I found the advent of the medical cannabis movement there a unique opportunity to explore how medicines are legitimized with both scientific and moral authority, and how that authority is constructed. Research on the potential medical benefits of cannabis is usually stonewalled in the United States, and it is legally problematic for staff at recreational shops to speak freely about it. Therefore, medical cannabis patients often resort to research on the internet, or attend local educational/activist events. (As I discovered, the two are often inseparable.) “Dr. Mary Jane, Her Patients, and the Evergreen State” is the culmination of the fieldwork I did at three such events in the Seattle area. Although they were of different kinds and had different audiences, the discursive commonalities throughout reveal a contested position keenly experienced by the medical cannabis movement between community and industry, the counterculture and the mainstream, the holistic and the biomedical. A substantial part of my research is informed by scholars’ previous historical analysis of the origins of the War on Drugs, as well as the scientific, legal, and political backgrounds of anti-cannabis government actions generally. However, medical cannabis laws vary greatly from state to state, and with that in mind I chose to confine my scope to the context of Washington State. The legalization of recreational cannabis with the passage of I-502 in 2012 had negative repercussions on medical cannabis patients’ access to products and information. Although no ethnographic research on Washington’s medical cannabis community pre-I-502 exists, the impacts of the law can be still be felt in the narratives medical cannabis advocates, educators, and patients – rather non-exclusive groups – consequently tell.

Although my research mainly falls in the field of medical anthropology, it is necessarily interdisciplinary, with great overlap with the history of science and disability studies. Developments in American and Washingtonian cannabis law have never occurred in a vacuum, and the stories of the science and politics behind them are more complicated and intertwined than I suspected when I first began this project. And in the study of medicine, especially a medicine spearheaded by people with disabilities, one cannot ignore the illnesses the medicine is intended to treat. The medical cannabis movement has powerful implications for the study of developing medical industries, public health education, and social movements overall.

Mekdes Assefa

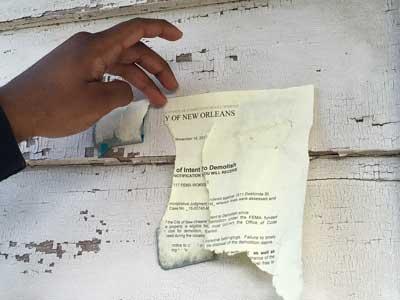

During my summer research, I returned to New Orleans once more to my partner’s neighborhood to canvas for any infrastructural changes since I had been there a year before. I also considered Katrina Archives from the local newspaper and visited several museums. Based on my visit, progress in the lower 9th Ward seemed frozen in time. Not much had changed since Katrina stopped being a hot topic in the media, and money to help recover poor Black communities had stopped a long time ago. I realize now that the

immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and the flood that ensued had been largely covered in the media, whether accurately or not.

Now, I would like to directly analyze the systems and institutions that were put in place to help the recovery efforts such as the Road Home program/FEMA trailers, Education/school system and the criminal justice system and how these systems set in place to help, harmed the community. Largely I am trying to answer the question of why the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans still looks like Katrina occurred a year ago, when in actuality it happened 12 years ago. As I grow this paper from a seminar paper to a thesis, I would like to delve into the sociological discipline and base my Thesis on race theories such as Power-conflict theories because I see this frozen progress as a tell-tell sign of not only systemic and institutional neglect of poor Black American in the Lower Ninth ward but also intentional harm of Black people in the entire country.

Anais Levin

This summer, I made use of the Emeritus grant provided by the Anthropology department to continue my archaeological research with the Belize Valley Archaeological Reconnaissance project. The goal of this summer’s excavations in the Settlement of Lower Dover was to understand how the settlement changed with the rise of the polity of Lower Dover. While the polity rose in the Late Classic Period (500-800 AD), the settlement, where most of the population lived, had been present since the Pre-Classic Period (200 BC- 150 AD) and remained populated to the Post Classic (900- 1200 AD). Therefore, by examining households from before and after the Late Classic Period, we can understand how the rise of the polity of Lower Dover, and, therefore, of a powerful elite, affected the commoners and intermediate elites that lived on the settlement.

My specific part in this research was the analysis of the lithic materials from the households. Through the analysis of these materials, we can increase our understanding of the economy of households: were they producing stone tools at the site or were they importing them from someplace else? Did this dynamic change after the rise of the polity? These are questions we hope to answer with the statistical analysis of the data collected this Summer. I intend to conduct statistical analysis this semester, and present my findings at the SAA meeting next Spring.