Defying Darkness

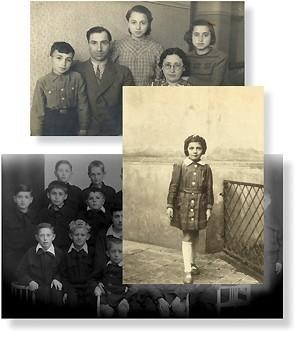

Three Children Who Survived the Holocaust

Before the Nazis invaded in 1939, about 1 million Jewish children lived in Poland. After the war, they had virtually disappeared from that country — fewer than 5,000 survived. The odds were not good for Jewish youngsters in Eastern Europe. Too small to work, they were usually killed immediately by the Nazis. Most who survived spent the war in hiding.

The brutality of the Holocaust is considered one of the worst atrocities of human history. How could it be said that anything good came out of such malevolence?

Yet the good can be found in those who survived. In this piece, you will meet three Grinnellians who survived the Holocaust as children: Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies Harold Kasimow, Celina Karp Biniaz ’52, and Sam Harris ’58. Rather than being overwhelmed by the evil they met at such a young age, they have chosen to see and be a part of the light of the world, rather than the darkness.

As one survivor said, “Hatred is akin to evil. I don’t want to be a person who hates.”

The Grave

Harold Kasimow’s earliest memories are of living in total darkness and silence, with no room to move and very little to eat.

Kasimow, his parents, and his two sisters spent 19 months and 5 days hiding from the Nazis in a hole dug in the floor of a cattle barn, covered over with boards and straw. He was 4 years old when they went into hiding in the hole. They called it the grub, which means hole. Sometimes, they even called it the keyver — the Yiddish word for grave. “We were already buried there,” Kasimow says. “If something happened, that could have been our grave.”

“I never saw the sun,” he remembers. “It was all strange to me when I got out. I’d never seen the light. I’d never been out of the hole. It was always pitch black.”

Kasimow was born in a small village about a hundred miles north of Vilnius, which is now the capital of Lithuania. At that time, it was part of Poland. His father, Norman, was a fisherman and a prosperous businessman who owned houses in two villages, one in Turmantas, which is now in Lithuania, and the other in Drysviaty, which is now in Belarus. He was well known and liked in the area. “He treated people with dignity,” Kasimow says.

“My father was quite a heroic figure, actually,” Kasimow continues. “He had very good relations with the people in the surrounding area, including non-Jews, many of whom were willing to risk their lives to help him.”

Kasimow’s family was one of only five Jewish families left in the village after the first year of German occupation. All the others had been transported to concentration camps or killed on the spot. Thousands of Jews in that area were simply shot. Kasimow’s maternal grandmother was one of those taken away. “I was very close to her,” Kasimow says. “They took her, and she was killed.”

In April 1942, the local priest came to warn Kasimow’s father that they should hide or run; he had learned that the Nazis planned to finish off the last few Jews in the area. Eventually, 95 percent of the Jews who had lived in that area of Poland before the war were killed. Virtually no children survived. The few who did survive did so with the help of Polish Catholics, Kasimow says.

A Father’s Heroism

Through sheer determination, Kasimow’s father kept the family alive. “He just never gave up under any circumstance,” Kasimow says. With three children under the age of 8, the family’s options were limited.

“My father knew the area very well,” Kasimow explains. “A lot of people would not turn him in, would even give him some food.” For a time, the family moved around, hiding in the forest and in attics and barns. In early 1943, Kasimow’s father persuaded a farmer, Wladislaw Piworowitz, with whom he had a working relationship, to allow the family to hide in the ground under the cattle barn. For the farmer, it was not an entirely altruistic act.

“My father promised to give him all the houses that he owned,” Kasimow explains. “Nobody expected that the war would go on as long as it did. But once we were there, he was stuck with us. There was nothing he could do. He was afraid to turn us in.” To do so would have been fatal for all involved.

Kasimow is grateful for the risks the farmer and his family took. “He was in that very horrible situation, but you know, he did risk his life, and the life of his family.”

The hole in the floor of the cowshed was big enough for the family, but with little room to move. A hole within the hole, covered with straw, served as a latrine. Kasimow’s father dug a tunnel to the potato cellar of the farmhouse. Through it he was able to slip out at night to find food for the family. Food meant bread and water, and not much of that.

The family had to stay quiet to avoid being discovered. “We were supposed to be silent and not even talk,” Kasimow says. He remembers an incident when a Nazi patrol with dogs came to the farm. “Somehow, maybe the barn was open, and maybe a dog smelled something,” Kasimow says. “It was probably a German shepherd, and it started to get excited. I know the soldiers had started walking away and just called him off. No one imagined that there was a Jewish family alive in this community, that there was anybody to find any longer.”

Into the Light

In the summer of 1944, the Russians liberated 6-year-old Kasimow and his family. “There was a kind of euphoria,” he says. “They were not persecuting Jews yet.”

Besides euphoria, Kasimow remembers being amazed by the world he saw. “I remember seeing cows eating grass. Light — I didn’t know it existed, actually,” he says. “After nearly two years in the grub, everything seemed so unique and strange and amazing.”

Nineteen months of near starvation and little or no movement had taken their toll on the children. “We were like skeletons,” Kasimow says. “My sister, who is two years older, couldn’t walk. … My father carried the two of us in a sack for awhile.”

It was still dangerous, for civilians as well as soldiers. “There was still shooting going on,” Kasimow says. “I was almost killed at that point. Someone shot off not the head, but the hat of the driver of a wagon my father put us on.”

Kasimow’s parents decided to leave the area where they had lived before the war and travel to the American-controlled zone. “My father’s brother was with us at the time,” Kasimow remembers. His uncle was a guerrilla fighter who survived the war and now lives in Israel. “We were stuck on a train,” Kasimow remembers. “Somehow we got disconnected from the rest of the train, and we were just left in the country, somewhere near Lodz. A group of local men came and tried to get into the car. I remember my father standing at the door with a piece of iron in his hand. His younger brother was able to crawl through a window of the train car and get the police,” Kasimow says. “They came and said, ‘OK, boys, break it up.’ There were many such incidents after the war.”

Once the Kasimow family reached Germany, they lived for about three years in Bad Reichenhall, a large displaced persons camp in a Bavarian resort area. The camp was a huge improvement over what the family had endured, Kasimow says. “Although we lived in crowded conditions, we had enough to eat,” he says. “We were free. Ultimately everybody left. Most people went to Israel, some went to Latin America, some even to Australia. In order to go to America, you had to have a sponsor.”

The Promised Land

It took time to find someplace to go. Immigration laws in the United States limited the number of immigrants who could come to the States. “We had my father’s sister to guarantee that if we came, she would support us,” Kasimow says.

When Kasimow was 11, the family traveled to the United States aboard the General Muir. The journey took 10 days, during which time many people suffered terribly with seasickness. “Everybody was sick,” Kasimow remembers. “I was the only person who went to the kitchen to have breakfast! They gave us oranges, which is probably the first time I had an orange in my life.”

Kasimow remembers the very day they sailed into New York Harbor — August 23, 1949. Though he was 11 years old, he looked like a 7-year-old. “I was very tiny,” he says. “I’m actually the shortest male in the family, because I guess those were key years when I didn’t grow.”

The family settled in the Bronx, where Kasimow attended Salanter Yeshiva, a Jewish day school, and sang in a professional choir. He played handball with the neighborhood kids. “I remember being quite happy,” Kasimow says. “Except for my own experience, I didn’t know about the Holocaust. My parents didn’t speak about it to us children, only to other adult survivors. I think a kind of survivor’s mentality grew gradually as I got to know more and more about what actually happened, not just to me, but what really happened to the Jews in Eastern Europe.”

Kasimow went on to Yeshiva University High School and then to the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, studying Hebrew literature and the Jewish tradition. “There wasn’t anything being offered on the Holocaust. The Jews basically didn’t speak about it,” Kasimow says. He went on to graduate school at Temple University, and came to Grinnell in 1972 to join the faculty in religious studies. When Gates Lecturer and Holocaust writer Emil Fackenheim came to Grinnell the same year, Kasimow began to examine his own past.

Even then, he rarely spoke of being a Holocaust survivor. He didn’t introduce topics related to the Holocaust into his classes on Judaism until about 1980, focusing instead on traditional Judaism. “There is 4,000 years of Jewish history preceding the Holocaust,” he explains. “You shouldn’t make the Holocaust the central event in Judaism.”

The little boy who lived in darkness and silence has become a respected religious scholar and a man of peace. Kasimow has devoted his career to encouraging dialogue among the world’s religions. His mentor and teacher, Abraham Joshua Heschel, inspired him to promote interreligious dialogue. Heschel provided guidance that helped Kasimow find peace — within himself, and with the world.

Kasimow’s work as a scholar has carried him around the world, forging close friendships with colleagues of many other faiths. One of those friends, the late Brother Wayne Teasdale, asked Kasimow to contribute his personal story of survival to Teasdale’s 2004 book, Awakening the Spirit, Inspiring the Soul: 30 Stories of Interspiritual Discovery in the Community of Faiths. “We became very close,” Kasimow says. “He was an authentic spiritual teacher.” He titled his contribution to the book “To Be a Mensch.” It was the first time he wrote about his Holocaust experience. Kasimow’s oldest sister, Rita Kasimow Brown, wrote a book titled Portrait of a Holocaust Child, which focuses on the time the family spent hiding during the war.

Twice during his career at Grinnell, Kasimow taught a class on the Holocaust. Only twice, he says. “It was just too painful. I thought it was an important course, and the students were very serious, and really did their work,” Kasimow says. “I put a great emphasis on the actual diaries of survivors.”

It was during this course that Kasimow told the students that he was in Europe during the war. But he didn’t then define himself as a Holocaust survivor. “Normally, I don’t lecture on the Holocaust,” he says. “I talk about topics related to interfaith dialogue, with a special emphasis on Abraham Joshua Heschel and Pope John Paul II. That is really my work. Only recently have I begun to realize that my work is related to my experience as a Holocaust survivor.

“Things are beginning to change for me. Last year, for the very first time in my life, I spoke at a synagogue on Holocaust Memorial Day. I’m opening myself up to the impact of my early experiences.

“I guess I’m actually ready now to tell my story,” Kasimow says. “I’m moved by the compassionate people I’ve met — a lot of compassionate people. During World War II, there were many Polish people who were involved in saving my family.” Kasimow says. “I’ve been back to Poland three times, and I’ve experienced nothing but real affection from the Polish people I’ve encountered. I am deeply grateful for that.”

When Kasimow was a boy, he didn’t understand everything that was happening to his family. He didn’t know why the Nazis wanted to kill them. He admits that even now, some 60 years later, he still doesn’t understand that sort of hatred. “I just don’t,” he says. “I don’t understand such hatred. And I guess I’d have to say I personally have never experienced it. I’ve been very lucky.”

‘Let Me Go’

Celina Karp Biniaz ’52 has looked evil in the eye.

She was only 13 when she and her mother ended up in Auschwitz. Their train, which they had thought was bound for relative safety in Czechoslovakia, took a nighttime detour, and the rail car full of Jewish women somehow arrived instead in Auschwitz — the most notorious of all the Nazi death camps.

At Auschwitz, Biniaz was separated from her mother and with some others was paraded in the nude in front of Dr. Josef Mengele, who was often referred to as the Angel of Death.

He pointed his finger, Biniaz remembers. One way meant life, the other, death. The first time, Biniaz was directed to the death line. Then he went through the line again.

“I just said three words in German,” Biniaz remembers. “Let me go.” She ran out of the room and escaped.

A Life Shattered

“I was 8 years old when war broke out,” Biniaz remembers. Before the war, she lived a happy, relatively privileged life in Kraków, Poland. Her parents were both professional accountants, and the family enjoyed a comfortable middle-class lifestyle. Biniaz attended a private kindergarten in Kraków, and then went to public school for first and second grade.

In 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, and Biniaz’s beautiful cultured life was shattered. Jewish families were forced out of their homes and herded into the ghetto. All the nice things her family had worked for were sold, and their sense of security was crushed. Former neighbors now wore swastikas. Education was forbidden for Jewish children.

As professionals with essential jobs, Biniaz’s parents left the ghetto every day to go to their jobs. They worked in the office at a factory where uniforms for the Wehrmacht were manufactured, under the management of Julius Madritsch — a close friend of Oskar Schindler, the rescuer of Jews made famous by Steven Spielberg’s film Schindler’s List.

Biniaz’s parents feared leaving their daughter alone in the ghetto all day while they worked, so they arranged for their taller-than-average child to get a “blue card” to allow her to work outside, too, although she was officially too young. She did various jobs, but more important, she was out of the ghetto and away from the Nazi roundups and killings, at least during the day.

In 1942, Madritsch’s factory was transferred into Plaszow, a Nazi labor camp. Jews who testified at the war crimes trials after the war remembered Camp Commandant Amon Goeth as a cruel and sadistic man. With his sniper’s rifle, he picked off children at play in the camp — for amusement. Torture and vicious killings were everyday occurrences. Poldek Pfefferberg, one of Schindler’s Jews, recalled Goeth this way: “When you saw Goeth, you saw death.”

Schindler’s List

Into this hell stepped Oskar Schindler.

There was perhaps no more unlikely hero. Schindler’s List author Thomas Keneally describes him as an opportunistic bon vivant and businessman at the war’s outset, a man who set out to exploit cheap Jewish labor and make his fortune. A master of bribery and a greaser of palms, Schindler used his connections to secure contracts with the Nazi government for his own profits.

And then, for reasons no one really understands, Schindler changed. He began to use his money for the good of his Jewish workers, buying them food and bribing guards to protect them. He established a separate sub-camp for his factory within Plaszow, and insisted his employees sleep inside to save time in transport. The truth is, within this sub-camp, “Schindler’s Jews” were kept safe from Goeth’s atrocities. Madritsch’s employees, though they were not in the sub-camp, enjoyed some protection as well.

“At first … [Schindler] wanted to enjoy the war and make money,” Biniaz says. “Why he changed and why he did what he did, I don’t know.

“He kept us safe … That’s what’s important.”

Into the Monster’s Face

In 1944, Plaszow was dissolved. “They knew the Russians were coming,” Biniaz says. Schindler devised a plan to move his factory to safety in Czechoslovakia, along with all his Jews.

“He wanted Madritsch to join him,” Biniaz recalls. But Madritsch had had enough and refused. Schindler had room for a few more in the transport to Czechoslovakia, so he instructed Madritsch to add some names to the list. Biniaz and her parents were placed on the list. It was a stroke of luck that meant life for the three of them.

Men and women were separated for the journey, and the men reached their destination without incident. For Biniaz and the other women, however, it was a horror that still haunts her dreams.

“Somehow, we were sidelined to Auschwitz,” Biniaz says. She remembers the stench of the place — the smell of burned bodies. When they arrived, she and the other women were told to undress and shoved into the shower room. They all knew what it would likely mean: death from the ceiling. When water, not gas, came out of the showerheads, they gasped their relief.

“That was so frightening,” Biniaz says. “But, oh my goodness, we were saved!”

They spent about four very cold weeks in October and November at Auschwitz before Schindler was able to bring them to the factory in Czechoslovakia. The factory there made components for V2 rockets. Schindler told his employees not to sabotage the munitions, for fear his plan to save them would be uncovered.

Mrs. Emilie Schindler holds a special place in Biniaz’s memory. She came to the infirmary at the camp in Czechoslovakia each day at 10 a.m. with extra rations. The extra food helped keep them alive. Even under Schindler’s protection, everyone suffered malnutrition. At the end of the war, Biniaz weighed only 35 kilos — 77 pounds.

At one point, the S.S. commandant from Plaszow, Amon Goeth, visited the factory in Czechoslovakia. “We were lined up to greet him, and Schindler walked through with Goeth,” Biniaz remembers. Always, always, in the death camps, the prisoners kept their heads down — to meet the eyes of a Nazi could mean being singled out for whatever horror was next.

At that moment, however, Schindler’s Jews had begun to feel almost safe. The war would soon end, and they had faith that Schindler would keep them safe. Biniaz raised her head and looked Goeth straight in the eye.

“It was a good feeling to be able to look the monster in his face,” she says.

A Rebel with a Cause

Even after liberation (which brought with it “an eerie feeling,” Biniaz remembers), Poland was not safe. She and her parents returned to Kraków, hoping to find family members, but there were none to be found. In September 1945, the Karp family left Poland and made the trek to Germany, where the family spent two years waiting for visas to the United States. Biniaz’s uncle in Des Moines, Iowa, sponsored the family.

Feeling as if she had no education whatsoever, Biniaz was anxious to catch up on her studies. “It was incredibly important for me,” she explains. Biniaz’s family sent her to study with a 90-year-old German nun, Mater Leontina. It was a great blessing for the wounded young woman. Mater Leontina’s kindness and wisdom helped heal Biniaz’s spirit, as well as nurture her mind.

“She accepted me for what I was,” Biniaz remembers. “She showed me things … changed my feelings about the whole situation.

“You have to move on,” she explains. “Some dwelt upon it. … You’ve got to end hatred and prejudice somewhere, you know.”

While the family awaited their visas in Germany, they happened to meet Oskar Schindler on the street. He recognized them and greeted them with visible joy. “He stopped us and chatted,” Biniaz remembers. “He was a wonderful, wonderful human being.”

After the war, Schindler was left penniless, all his money having been spent to save his Jews. He tried his hand at other businesses but without success. Finally, he emigrated to Israel, where he lived out his life.

“He is a very interesting person, a rebel with a cause,” Biniaz observes.

Moving On

Biniaz was 16 when her family finally boarded the ship that would carry them to the United States. She remembers how she was struck by the beautiful neon lights of New York City when they arrived in June 1947, and later, the peaceful settings of Iowa.

Biniaz, anxious to go to school, attended North High in Des Moines. She found she was not so far behind. “I loved it!” she says. “I just loved it, and I was truly accepted by the children.”

A teacher there was a graduate of Grinnell, and encouraged Biniaz to apply. She won a scholarship and soon found herself studying on Grinnell’s peaceful green campus.

“I loved the atmosphere of Grinnell,” she says. “It renewed my life. … Grinnell was just wonderful to me.”

But as so many Grinnell students discover, the life of a Grinnell student involves a lot of study. “I had to work very hard because my English was not great at all,” Biniaz says. “That first year was intense, let’s put it that way!” She also worked at a variety of on-campus jobs. “I had all kinds of jobs — you name it, I did it!”

A class with Professor of Philosophy Neal Klausner (“a delightful human being”) was life-changing for Biniaz. Though he knew little of her personal story, Klausner helped her begin to think through the terrible experiences that had obliterated her childhood and could easily have destroyed her adulthood.

She chose to major in philosophy, and the study helped her deal with her personal demons. Still, she did not talk about her experiences as a Holocaust survivor. Biniaz chose not to dwell on the nightmare. She was moving on.

Finding Her Voice

Biniaz continued her study of philosophy on scholarship to Columbia after graduating from Grinnell. There she met the man who would be her husband, Amir Biniaz, a dentist. They married and had two children, Robert and Susan, and later, four grandchildren.

Biniaz taught for many years on Long Island, where the family lived. She focused on children who needed special help. “I felt I had to give something back.” She taught for 27 years, and loved it. She and her husband now live in California, near family. “It’s been very good,” Biniaz says.

For 40 years, Biniaz did not speak of her Holocaust experiences. She had lost her childhood and her faith. After seeing little children brutally hurled against a wall and killed in the camps, her faith was gone. “There was no way that I could accept a benevolent deity,” she explains. She is today very much of a humanist, Biniaz says.

In 1993, a film opened the doors of her memory. Steven Spielberg’s acclaimed film, Schindler’s List, told the story of Oskar Schindler and his transformation from disreputable businessman to heroic rescuer of 1,200 Jews. Biniaz credits Spielberg with her new ability to talk about the past. “He gave me a second life — he gave me a voice,” she says. She was interviewed about her experiences for a documentary released with the DVD version of the film.

Still, she chooses not to dwell on what happened to her as a child. “I try not to think about it,” she says. She has worked hard to avoid burdening her children with guilt for what happened. With her family, she took a trip to Poland in 2006. She visited the factory where she used to work, which is now a museum, but she didn’t want to visit Auschwitz. The rest of the family went without her, and her 10-year-old grandson came to her after the visit. “Grandma, it was horrible,” he told her. “But everyone should see it.”

Does Biniaz understand hatred of such virulence as what she saw as a child living through the Holocaust? Perhaps. “It comes from having less than others,” she says. “Prejudice comes from not knowing, and from fear.”

Fear is something Biniaz understands, too. “The one emotion that has stayed with me in life is fear — fear of authority.”

Biniaz’s own philosophy is simple and beautiful: “Don’t hate. Try to live with your neighbor. Accept people for what they are. Nobody’s better than anybody else.”

It’s clear, when you see Biniaz smile: Hitler tried, but failed, to destroy her spirit.

The Darkness is Not Sufficient

Sam Harris ’58 is a man of hope. He sparkles with it, like the sun emerging from the clouds.

A child survivor of the Nazi death camps, Harris is now leading the efforts to build a museum dedicated to educating people about the Holocaust. The Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center will open early next year in Skokie, Ill. Harris has committed years of his life to building the museum, which he hopes will counter the “Holocaust deniers,” who claim that the Nazis’ plan to exterminate the Jews never took place.

“The best way to solve a problem like this is through education,” Harris says.

Today he is an active spokesman who talks frequently about his experiences as a child. It wasn’t always so, however. As a Grinnell student and for a good deal of his adult life, Harris did not speak about the camps. “I wanted to put a cement wall around my head,” he explains. He had built a happy, prosperous life for himself and his family, and he put the past behind him.

With the help of his wife Dede, Harris was able to reclaim the memories of the child he had been. He even wrote a book for children about his experiences in the camps (Demblin and Czestochowa), titled Sammy: Child Survivor of the Holocaust (Blue Bird Publishing, 1999). He speaks frequently at schools, and his message is straightforward: life is good if you let it be.

Harris saw that the old Holocaust museum in Skokie was simply too small for the crowds of schoolchildren who wanted to visit. He remembers thinking, “We need a new museum, and I am the perfect person to do something about it.” With the support of his family, he has made the museum his priority.

“I wanted to pay back the good things that had been done for me,” he explains.

The new museum will be “spectacular,” Harris says. The board has hired award-winning architect Stanley Tigerman; Michael Berenbaum, project director of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.; and Yitzchak Mais, chief curator of the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City. The design takes a two-sided approach. Visitors enter on the left and move through the story of the Holocaust, beginning with Kristallnacht, “the night of broken glass,” and moving through the ghettos, the cattle cars, and the camps. There, says Harris, they learn of “all of those terrible things.”

But the journey doesn’t end there. “On the right side, we will emphasize positive things,” Harris explains. “In my opinion, a lot of goodness has come out of people due to the Holocaust.” The right side of the museum will tell those stories of hope.

An example, Harris says, is the story of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg. “He stuck his neck out and saved hundreds of Jews,” Harris says.

“That’s what we want to leave them with,” he explains. “Hope. … The darkness is not sufficient for me,” he says. He’s also proud of the special children’s museum for kids 12 and under.

Many survivors have donated their artifacts, and Harris, too, has a special object he will give to the museum, when he can part with it. It’s a little belt — the only thing he has from his childhood. He takes it with him when he speaks at schools, and when he tells the story of the little belt, there’s rarely a dry eye in the house.

“I am very, very attached to it,” Harris says. “You can understand why.”

He uses the cracked and broken belt to show that he himself is not broken — the human spirit is strong, stronger than those who would crush it.

“I want to make sure that what I went through doesn’t happen to any other child,” Harris says.

Originally published as a web extra for The Grinnell Magazine Summer 2008.

Read the full story of Sam Harris’ survival, Survival: Outwitting Evil, previously featured in The Grinnell Magazine.

You can also read One Man’s Odyssey: A Grinnellian’s Flight from Hitler, about John Stoessinger ’50.