Scientific Research from Home During the Pandemic Summer of 2020

How a biology professor and two students pivoted to make the best of a research opportunity

During a normal summer, Grinnell’s campus hums along to a different tune. Classes are over for the year, and students and faculty turn their attention to research.

But summer 2020 isn’t a normal summer. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, few people have been allowed back on campus. Which begged a question. If students couldn’t be on campus, could research projects still be done?

For some, the answer was no. But for more than 90 students, the answer was yes, because their projects could be done remotely.

That includes two students working with Vince Eckhart, Waldo S. Walker Professor of Biology, on Mentored Advanced Projects (MAPs).

“When I found out MAPs were happening at all, I was very happy about that,” says Bjorn Larson ’22, a biology major from Wisconsin.

“I was nervous it [the MAP] would get cut completely, but at the same time, I was supposed to work in a lab,” says Kate Tomczik ’22, a biological chemistry and studio art double major from Minnesota. “How could that possibly work? My mom’s a lawyer and my dad sells stuff. I have no science equipment at all,” she adds with a laugh.

That was a concern for Eckhart too. “What could they do in their houses that doesn’t take a lot of space, specialized instruments, or dangerous chemicals? I had to scramble for ideas for what would be feasible as well as what would still be informative for the research and maybe even produce publishable work,” he says. “If it’s informative and rigorously done, it still should be worth subjecting to peer review.”

He settled on seed germination — specifically the water physiology of seed germination. In his research on the distributions of plants in California, seed germination “seems to make a big difference in why species occur where they do,” he says.

Eckhart shipped his students seeds of known populations of a plant he’s been studying since the 1990s — Clarkia xantiana. He also sent them supplies: special seed germination paper, petri dishes, data-logging thermometers, and sets of plastic bottles filled with pre-weighed amounts of polyethylene glycol.

The chemical dissolves in water and makes the water less available, which mimics soils of differing dryness. It’s a method for simulating what would happen in nature for different rainfall and soil conditions.

Doing Mentored Research from Home

Working from home took some trial and error, Larson says. “It was tough at first to figure out how best to get everything set up.”

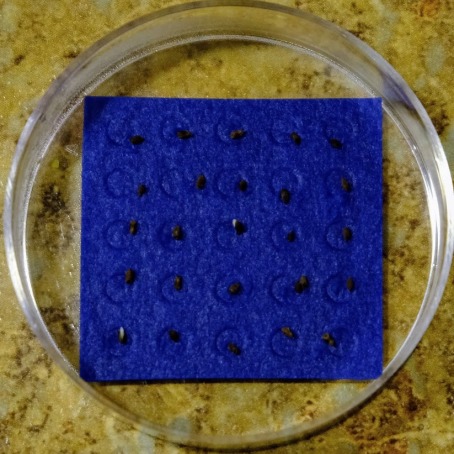

He and Tomczik did a small pilot test with one petri dish each in an upstairs room in each of their homes. One petri dish holds a square of blue germination paper with 100 tiny indentations to cradle each seed.

“That wasn’t getting the results we were hoping for,” Larson says. “It was probably getting too hot. Might have been getting too much light. That meant there was a lot of condensation because of the change in temperature. So water was condensing on the lids of petri dishes.”

They also tried the refrigerator.

“When I looked at [the seeds] later, they were all over the place,” Tomczik says with a smile. Her mom had moved stuff around in the fridge, unintentionally disrupting the experiment. “I thought, this might not work for me.”

They settled on their basements, where they found germination was most successful. For each of the multiple trials of their experiments, they check hundreds of seeds every 8 hours and record germination data, continuing for 280 hours (2 weeks). Meanwhile, the electronic data loggers record temperature automatically every 10 minutes.

Remote Research Works, But Community Is Harder to Maintain

Larson and Tomczik communicate twice a week with Eckhart via video chat. “I get my questions answered,” Tomczik says, “but I think it could be more fully developed if we were in person.”

Under regular circumstances, she and Larson would serve as each other’s lab assistants. They’d be able to interact with other MAP students on campus and learn about everyone’s research during weekly lunch meetings.

“It’s been hard not feeling as connected to campus,” Larson says. “The community aspect is lost, and that’s too bad.”

Due to the travel restrictions the College put in place, the students are also missing out on a field experience — 3 weeks with Eckhart in California, doing field research and seeing what that’s like, working alongside grad students, postdocs, and professors from other schools.

Although the research experience during the summer of 2020 has been challenging due to the pandemic, both Larson and Tomczik have learned a good deal.

“My scientific research comprehension has skyrocketed,” Tomczik says. She’s been looking up papers and articles to read to help write the final paper that’s due at the end of the MAP.

Larson admits that research from home during the pandemic has “been very different from a normal MAP experience,” but he believes it’s still a valuable experience.

“Diving deep into a topic that you don’t really know that much about, getting to focus on one specific plant and one topic in ecology is something that I think really helps to prepare for what maybe happens more in the real world,” he says. “It’s teaching a lot of the same skills about how research gets done.”